Aerial photography by Andro Loria: a look at natural treasures.

This interview was published on the 5th of March in French on Graine de Photographe Website.

Below is the original English language version:

Two white Cessna airplanes (10 and 12 o’clock) over glacial kettles (lakes). Edge of Mýrdalsjökull glacier, Iceland

Aerial photography is a fascinating discipline that offers a unique perspective on our planet. We discover breathtaking landscapes, which are exceptional to observe from this angle. After years of working in the scientific field, Andro Loria has been able to combine his love for nature and his technical skills to capture landscapes of rare beauty from the air. Aerial photography is now his specialty, even if he has previously experimented with many aspects of photography. His approach combines technical rigor and artistic sensitivity, offering spectacular views that reveal the grandeur of nature from a new angle.

With these images, Andro Loria also shares his connection with nature and aspires to transmit it, as well as the desire to preserve and protect it. According to him, “If people start to love nature more, there is a chance that they will protect it more, because we tend to take care of what we love.”

Discover our exclusive interview with photographer Andro Loria:

an immersion in the practice of aerial photography.

“Fireflies in a magic forest” - dry soda patterns, brine and water of Lake Magadi, Southern Kenya

What attracted you to photography?

It is a long story... :) I think it would be better to say that photography (the way I do it now) has found me and finally walked into my life at the right time, after a few less successful attempts :)

I grew up when photography was analogue, I remember having a small, fixed lens camera, which I used with a black and white film to photograph friends and pretty much what people use their smartphones for nowadays. It was fun to shoot but even more so to develop films, project them onto photopaper and then develop/fix prints. Seeing an image appearing out of “nothing” has always had a bit of a “magic” in it. I did not photograph much through my student years, albeit taking small camera with a couple of film rolls to my long-range kayaking trips. Being limited to using film was holding me from engaging more with photography then.

Nature’s palette - colours of the mineral-rich rhyolite mountains. Landmannalaugar, Iceland

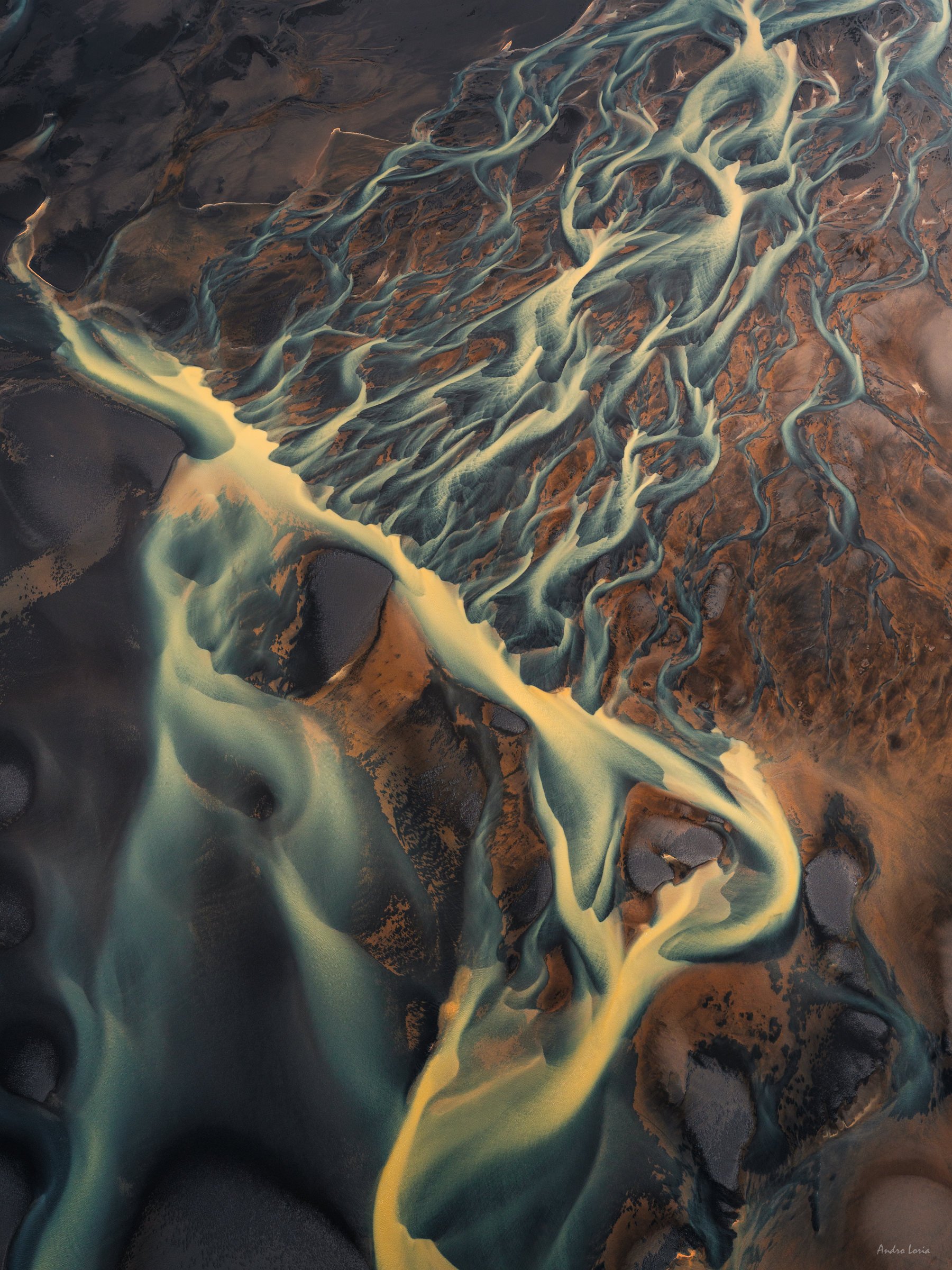

Three white birds (white specks, centre) line up over the convergence of glacial streams, western side of Vatnajökull, Iceland

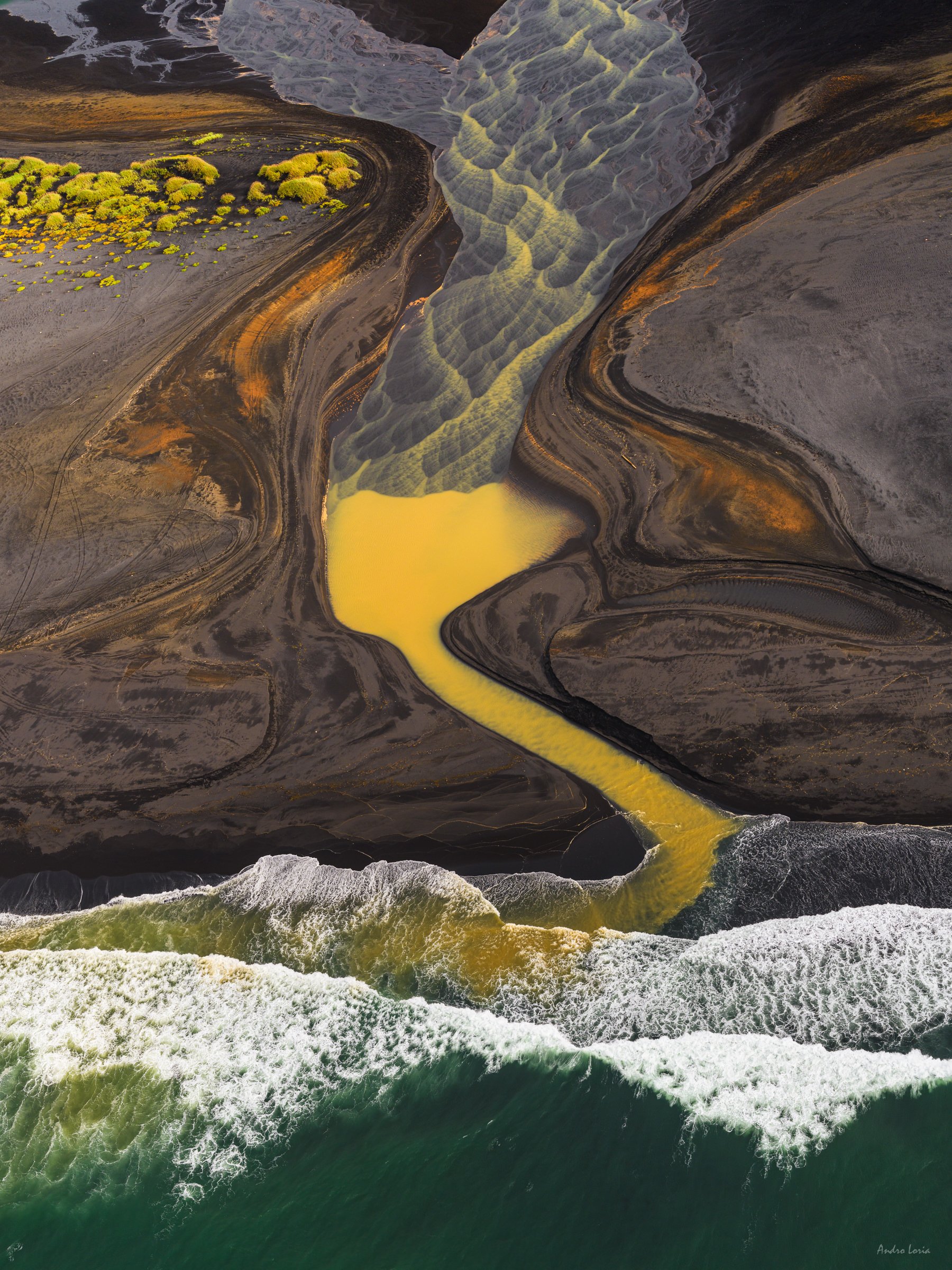

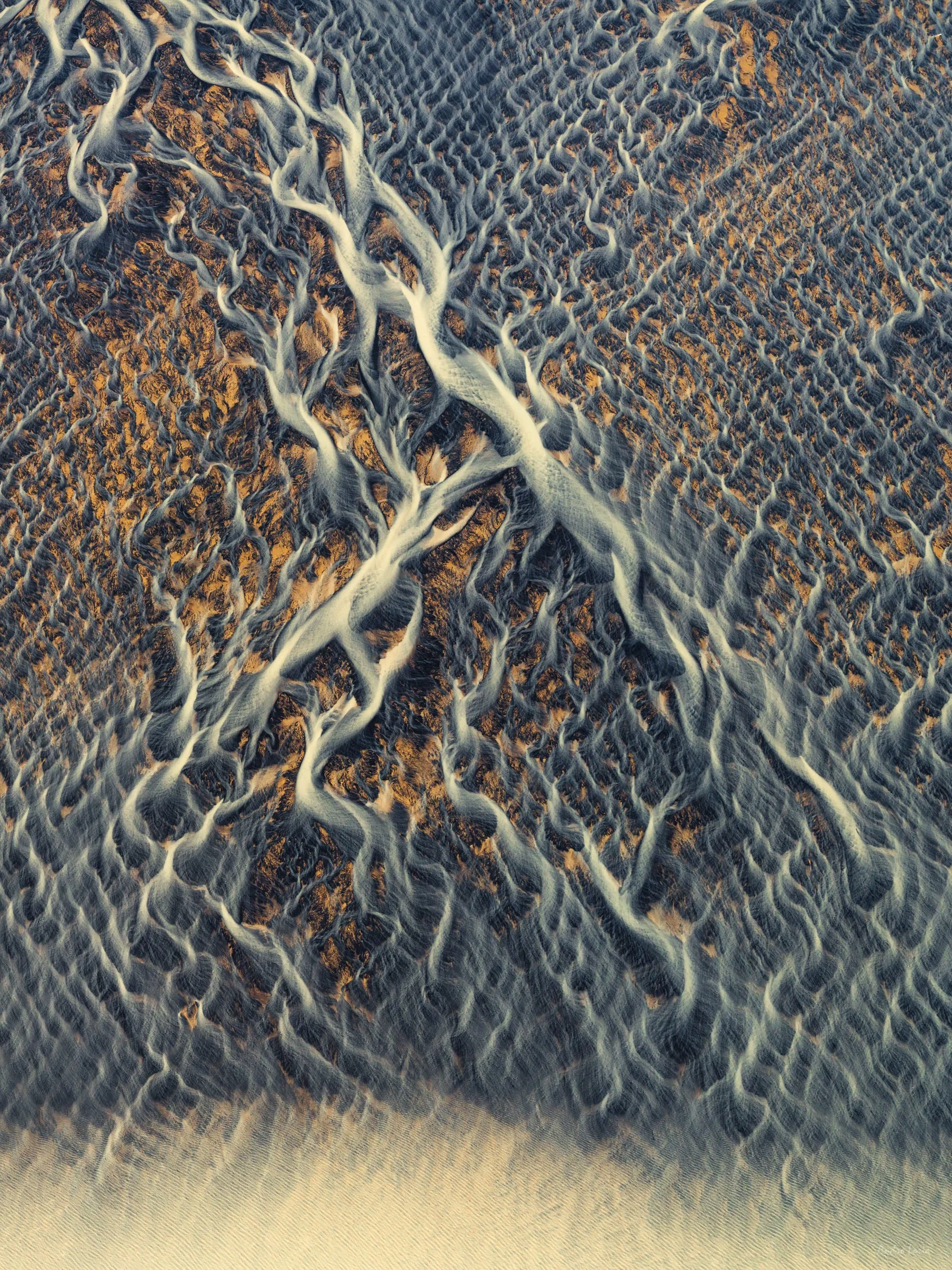

River patterns, South coast, Iceland, aerial shots from 2-3k ft, Cessna 172

Scientific laboratories and structural biology: a gateway to photography?

Those days my photography and image processing were restricted to the science laboratory environment, e.g., taking pictures of DNA gels, exposing/developing X-ray film to read DNA sequences etc. I then moved to the structural biology field and did a lot of 3D analysis of protein machines that protect our genomic integrity, so I guess that helped me to develop some sort of a 3D vision, that is how to observe/see an object from different angles and choose which side/angle would be the best to share with others to represent it.

I suppose I already had some training in that through technical drawing training in my student time, topography and navigational training on my travels, but my science work brought it to the next level. I also learned a great deal about digital imaging then and what high-end digital sensors are capable of.

At some point in my life, it become clear to me that I would like to have a bit more than my visual memories from the places I go and see, so about 12 years ago I got a couple of mirrorless cameras, which I quickly fell in love with. Also, with my science work entering period with less of experimentation in it photography became my new additional if not a prime creative outlet. A new field for exploration, observation and reflection.

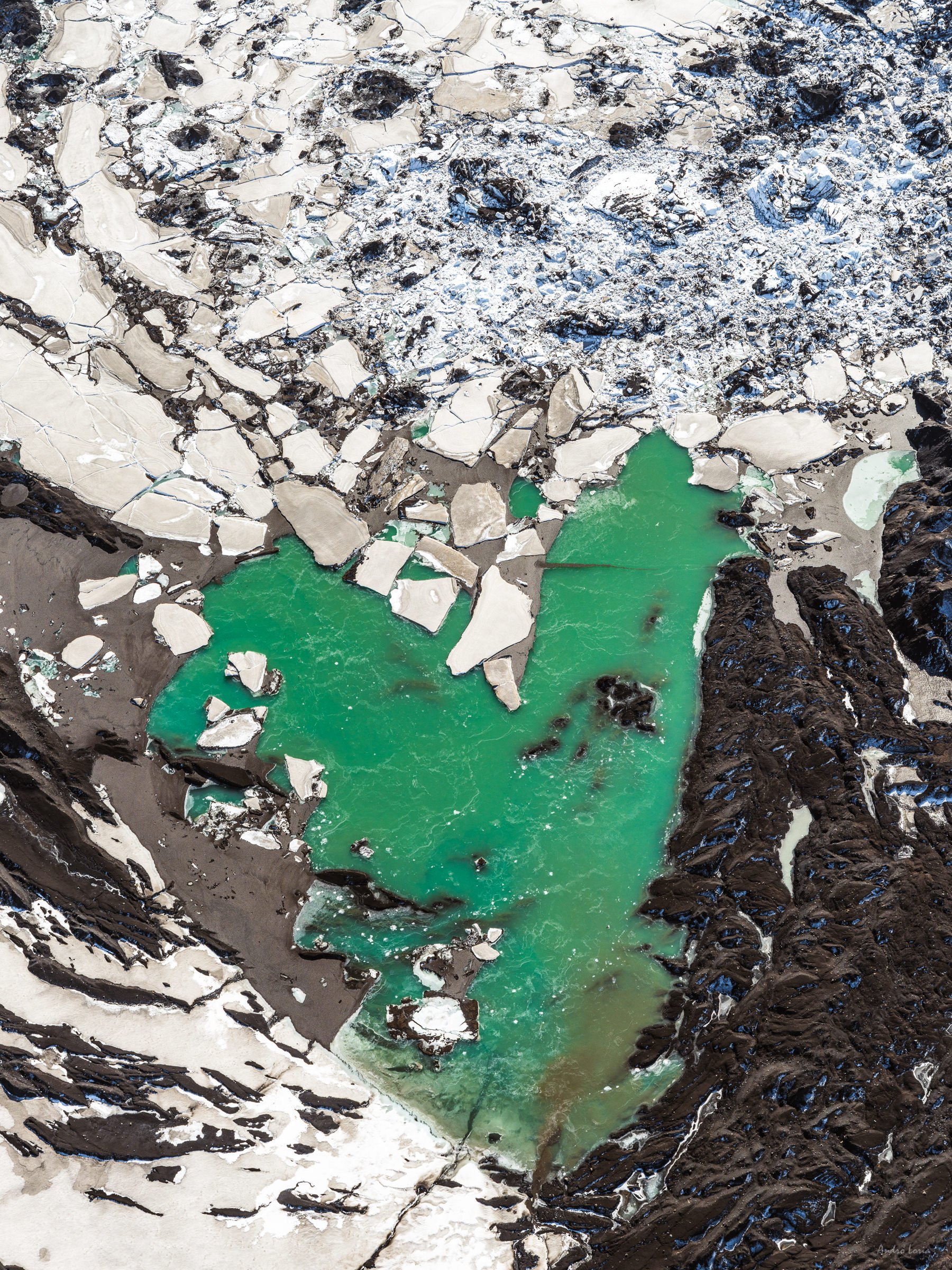

Colour kettles - glacial ponds at the edge of a glacier look like a kaleidoscope of colours. Kettles are small glacial lakes, formed by a retreating glacier. The colour of the lakes is provided by silt and minerals. Typically the colour starts from milky beige when silt particles are largest and goes all the way to clear blue when particles are smallest, so one can see the direction of water flow between these kettles. A flock of birds (arctic terns), white dots on the surface of the blue lake up left show the scale.

What is your connection with nature and what made you want to photograph it?

Well, we all are connected to nature one way or another. We are a part of it, I guess it is the biologist in me speaking :) When I was a child, I grew up in a small town on a hilly bank of a river with great views around it, there was a national park on the other side of the river and wild animals often crossed over, so on some mornings in winter it was fun to see who came to visit by reading the animals’ tracks on the snow. I would often come home after school and go for a forest walk in the spring/autumn or go for a ski run in the nearby woods with our family’s dog in the winter and of course spending whole days in the woods in the summer along or with my family or friends.

I guess for me after decades of travelling in sub-arctic regions, various mountains, all of which were with wild camping, I do have a strong bond with nature. You learn how to live in the wild, how to respect and love it. Seeing amazing vistas from mountains or rafting/kayaking down the white-water rivers gives you a sense of awe on one side, but also a feeling that you are a part of it, moving with it, breathing it in, sensing it in many ways. In addition, it is also hard to not see the changes that our planet goes through, with vast areas changing dramatically within our lifetime due to climate change and human activity.

Flamingos flying over the rain filled Lake Logipi, Kenya

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Bogoria, Kenya

I do not think there is anything that made me “want” to photograph nature.

I photographed many things when I started, architecture, black and white portraits in, a few years of street photography, even my friends’ weddings, but gradually it all came to the point that like with anything in life you start doing more (or trying to do more) of things you love most and for me that was nature photography, specifically aerial landscape photography. I suppose with age and experience I just wanted to focus on what I love doing most and do it more, so for the last 7-8 years it was non-stop aerial photography time.

Photographing nature takes me away from people (meaning too many people), flying gives mesome sort of a “meditation” if you wish, although the amount of visual overload one gets when photographing from the fast-moving plane or helicopter can hardly be described as a zen state with a fast endless conveyer belt of kaleidoscopic imagery coming your way from all sides.

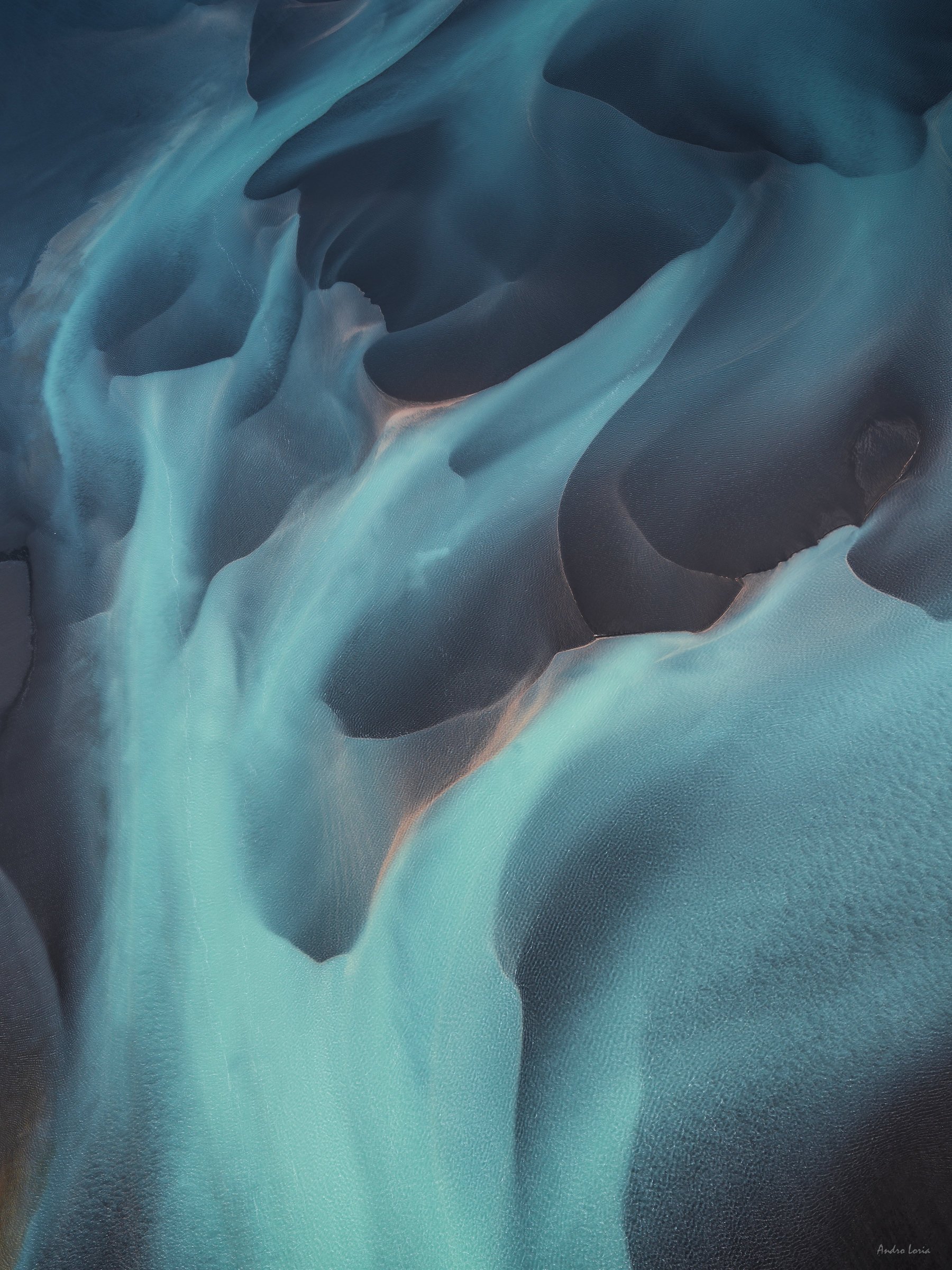

Glacial silk -silt and mineral coloured glacial streams look like silk ribbons when seen from 3000 ft above, creating a natural abstract. South coast of Iceland.

Flying provides an ability to see some out of this world’s amazing views, get a unique perspective, the ability to see things and areas in a different unfamiliar way, freedom, peace and getting to know some amazing like-minded people both pilots and photographers.

At the end of the day, I suppose we (as humans) try to protect and care of what we love, so I guess even though the images I make are primarily for the sheer beauty of those views it is also a way of protecting and keeping those amazing views as they are, in a documentary, memory card way of photography in our fast paced changing world, and also hoping that some people may get closer and bond to those places.

If they start liking/loving nature more then there is a chance they will protect it more, as we tend to care about what we love more too.

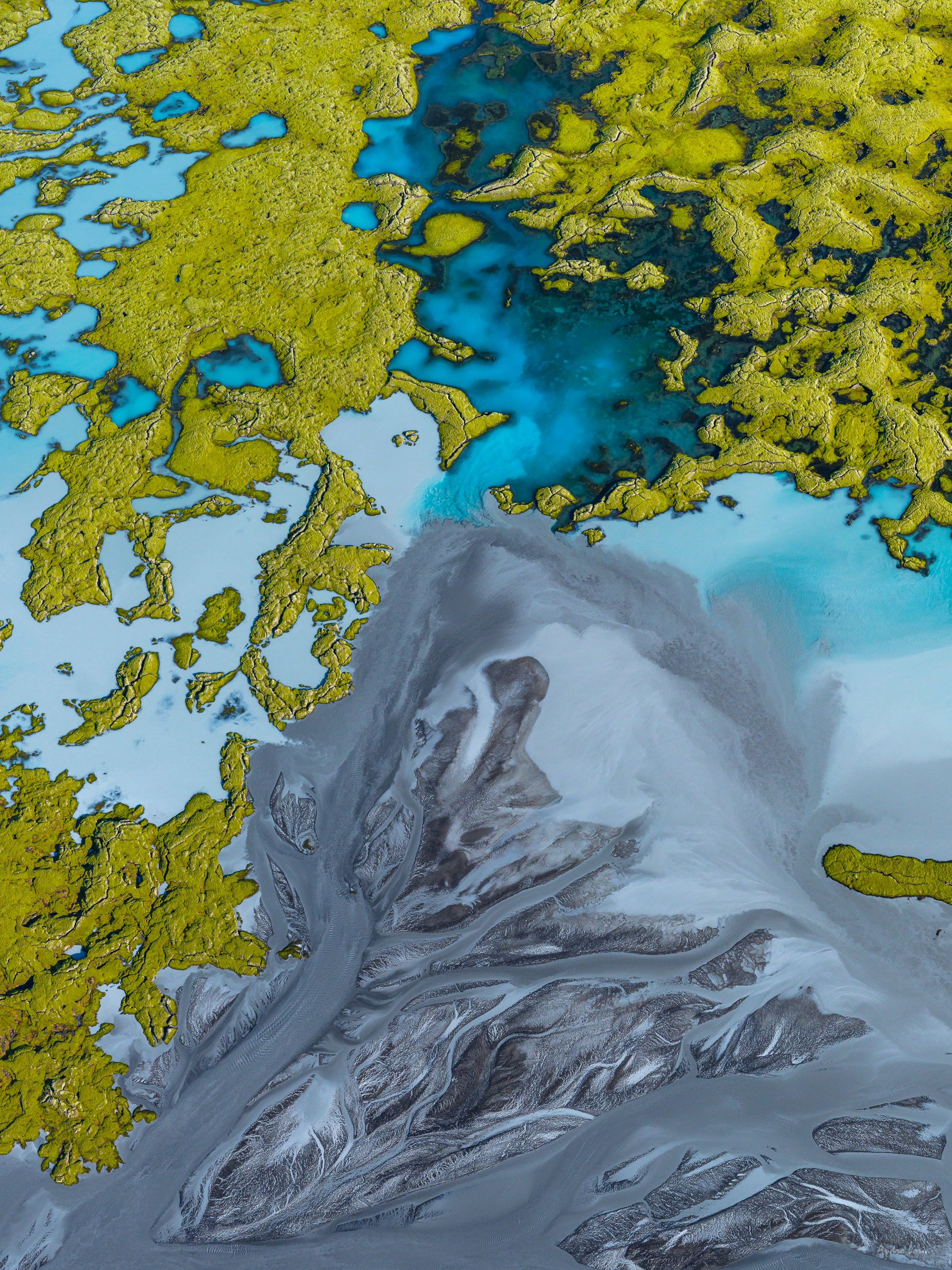

Oasis in summer - moss on the mountain slopes contrasts the blue of the crater lake and the silt-rich grey of Skaftá river during a glacial run in the Southern highlands, Iceland

Oasis in autumn (october) - sunlight lit moss on the mountain slopes contrasts the blue of the crater lakes, Iceland

In your interview for Fujifilm, you explain that you draw up a precise flight plan, either based on places you've already visited and spotted, for example on hikes, or when it comes to places you don't know, thanks to satellite images. How do you choose these places?

Yes, very true, a lot of planning is involved, albeit these plans do not always hold :) It all starts with having an idea to where I’d like to go/fly. I then would check other people images and descriptions of the area (if any) to get a better idea on seasonal changes and patterns. Most of my homework is done with Google-Earth, first identifying zones/areas of interest and specific points that could be of interest. That is then used to sketch a potential flight path to see as much as possible and at best light and/or tide level, which can then be used to estimate the flight length and thus fuel/time needed for it in a way that includes a couple of 360 degrees loops (laps) over every spot of interest. All together that timing should be within the flight fuel range and time allocated.

Four hours is a typical time of flight. Five to six hours or even seven hours is possible with a break and refuel stop. Then this all is shared with the pilot to assess and amend it with his/her knowledge of winds, weather patterns and forecasts. We always have two to three different flight options to choose from depending on the weather with one to be chosen a day before or early on the flight’s day depending on the weather – winds, rain, time of tides, cloud cover (base layer of clouds etc).

I mentioned that the pilot will have the final say to where and how we go for whichever plan we have and that means that the pilot will have the ultimate choice in deciding whether we fly into an area or not on the day of flying. There are some areas we had to fly, or rather attempt to fly to more than once, like two or three times in some cases. Even with a perfect forecast you may find that your destination point of interest is completely covered with clouds, or the base level of clouds is too low to have a proper top-down shot so you move onto another plan and area.

Interference -silt and mineral coloured glacial streams look like a giant glacial lace or a stretched Hessian-like mesh when seen from 3000 ft above. South coast of Iceland.

Aerial photography is a close-knit teamwork with the pilot.

You agree on communication words and gestures to be used, discuss pre-flight what you expect when you over a spot of interest etc. The pilot makes the final decision on whether to fly, whether to go into the zone of interest – it could be too windy and turbulent in a tight area between mountains or too low with winds pushing you down.

The choice of places comes from what I see on satellite images, from what I think I might see from my experience after flying/hiking in the area and thinking of how to capture it in a different way, e.g., fresh snow powder, dust beaten down by fresh rain giving away brighter colours of rocks. But I never really go for a specific shot that I have in my mind. It is always an open book; I do not like to overthink it.

As we say in science - we plan experiments but not the results, that is something to be seen and found out once we are there. The places that I choose are those that have nice patterns and some landscape features that will provide for 3D rendering with light and shadows. I currently try to revisit some places in Iceland in different seasons, seeing them in a different light and colour. After coming back from flights and seeing new places I always try to learn more on the area’s geology and nature, try to understand it more, learning why rivers or rocks have specific colours, what is the variation of patterns in the area brought by geothermal activity, seasonal changes etc.

Glacier's necklace - glacial pools (kettles) form a giant nordic "necklace" pattern at the edge of piedmont type glacier when seen from above - about 6k ft. Central highlands. Iceland

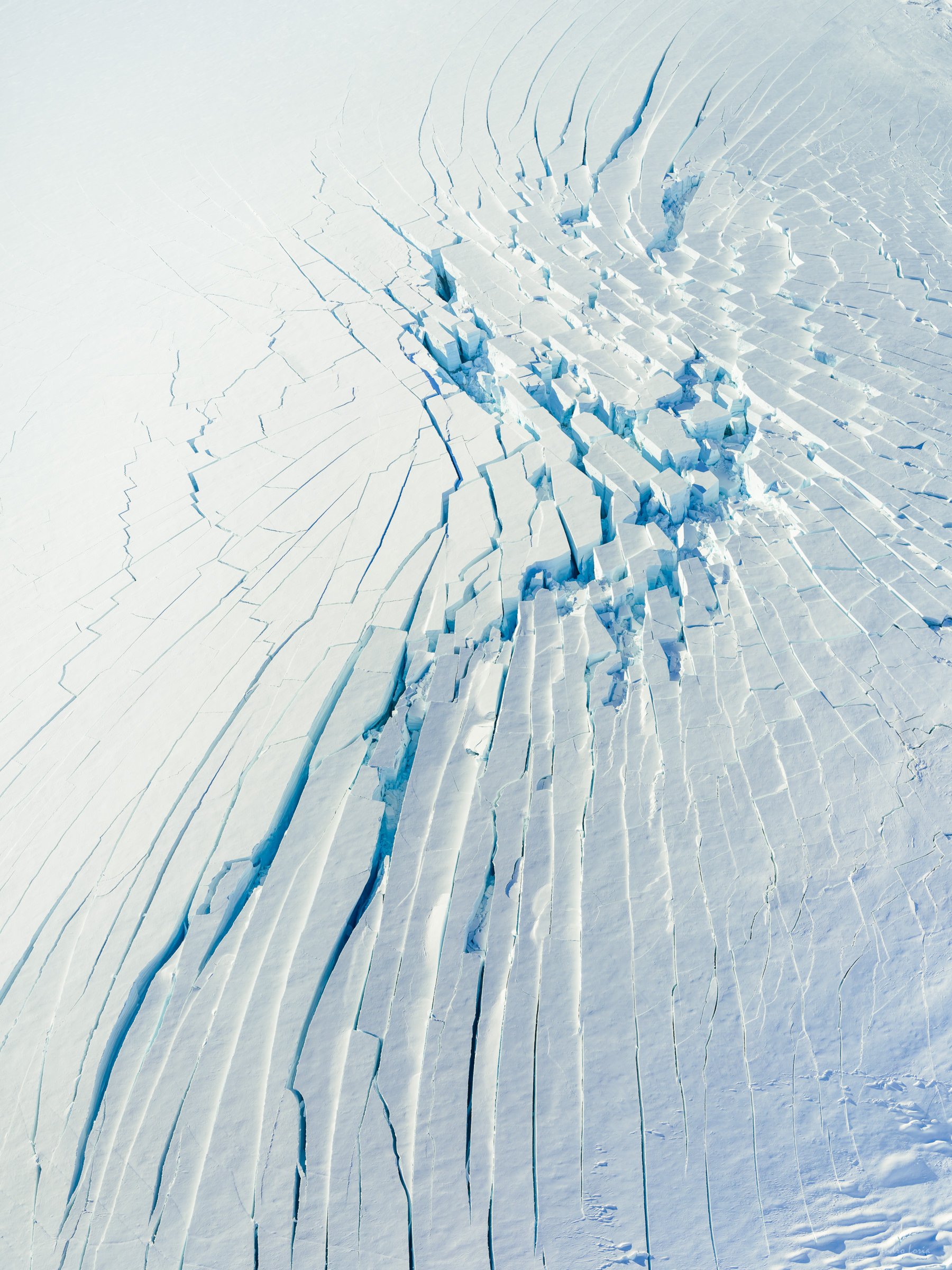

Giant ice troll swimming in a glacial lake :) The real story is that the Grímsvötn volcano, which is hidden under the ice cap of the Vatnajokull glacier, melted a couple of massive depressions. The heat melted an amazing blue lake, shown here (~300m across), full of bergs. Iceland

What catches your eye and makes you think it would be the ideal place to take these photos?

It is very good question, and the answer to it is - it is very changeable... it so much depends on the moment, my mood, light etc. One’s (and mine) way of seeing things evolves with time and experience. So many times, when flying in the area to photograph pre-planned spots/views I have made totally unexpected photographs and valued them more. And even more so on the way to those areas.

Aerial photography is very reactive, you cannot be “tunnel visioned” and go for a specific shot in your head. In that way you will miss a lot of shots, including the best possible ones. Interestingly, I find aerial photography somewhat resembles street photography in terms of reacting to what you see. You do not pre-plan an image, you fly, you explore, you reflect and you react with your camera. Your camera is constantly ready next to your eye, you pre-empt the situation, your mind learns to “foresee” whether that is a combination of light, colour and silhouettes in a street scene, or light and patterns in an aerial view, top down or angled, feeling the frame with the seemingly chaotic, but naturally balanced elemental geometry of nature.

On some occasions, you see great scenery, but you feel that something is missing, or the scene just feels too perfect, if I can say that, and often that extra element is a flock of birds that suddenly enters the frame to somewhat make it less organised and more natural, bringing some life into it, albeit looking a bit abstract for most as we do not typically look at flying birds from above. Typically, these best frames stay in your mind from the moment you see them and press the shutter, when everything clicks together and you just feel and know that...

Flying over a magic tree made of moss... planet Iceland, aerial shot from Cessna 172

Patterns of coastal streams at the Magadi lake area, Kenya

The landscapes you photograph from the sky appear abstract in the image. What do you like about this rendering?

It is true, the images that are taken from aircrafts, especially the top-down shots are very different, as they lose reference to scale, horizon lines and sense of perspective. Yet the term of abstraction is probably not a correct one, as they do exist, we just do not see those views and scenery. They are perfectly normal for birds, reflect the existent reality and only appear “abstract” to us humans as they do not reflect our typical way of seeing things in a lateral perspective. The same can be said about scientific images, they are so far away from our usual way of seeing things, yet the beauty of macro and microscopic worlds does exist. What I like about this unusual way of seeing and imaging is that it allows you to see the unseen beauty of the world, capture it for everyone else to see and feel like an explorer of a different world with constantly changing amazing imagery in front of your eyes and camera. And that is on a top of the flying itself, which is already amazing.

Glacial streams coloured by silt and autumn yellow moss combine into a natural abstract when seen from above, Iceland

Flamingos flying over soda brine patterns formed by winds on the Magadi lake surface, cloud reflections on the top of the frame. Magadi lake, Southern Kenya

From a technical point of view, is there a lot of post-production involved in your images?

I try to not spend much time on editing images. Most of my time is spent deciding which frame(s) I mark as best before editing them. A large number of images is as a result of taking photographs from a few laps flown over a subject, so there are some inevitable repeats, or at least frames that are similar to each other. Some frames could be affected by a strong reflection from water or ice, so unless I find them interesting, they are discarded. Out of a typical 2 to 3,000 images I bring from a trip, with about 1,000 images made in one day/flight I aim to keep about 10% of the strongest ones, which is a far superior amount when compared to what can be done on the ground within that time.

I would say a few minutes of post-processing per image is probably what it takes, just to adjust white balance - I always take shots of colour card and deliberately incorporate the airplane’s wing (which are typically white) into some frames, so I get a reference to whichever light condition I work with.

Dry soda and soda brine patterns at the Magadi lake area, Kenya

I usually underexpose for one or two stops depending on the light. It is easy with a digital camera, as I can follow the live histogram on my viewfinder. There could be a slight gradient drop for the top of the frame to compensate for the sky (if any) and/or a slightly brighter part of the frame due to the difference in light reflection (aerial perspective), sometimes a slight crop/rotation - I typically try to not have more than about 5-10% of the frame taken out. In most cases it happens is when a part of the wing or wheel enters the frame due to turbulence or an unexpected movement of the plane and/or camera. I do not need to change sharpness - the lenses I use are amazing, but I would adjust it for printing depending on the print’s output size.

I personally prefer a 4:3 aspect ratio, that is how I see things and it works great for aerials, so I rarely if ever use other type of frames. I stay clear from wide angle lenses, as I personally find anything wider than a 40-50mm focal length is too wide and I prefer making shots in a short telephoto range, between 60 to 70mm, so I do not have problems with distortions of scenery that would need to be corrected. I take shots at 70-90mm when photographing top-down views, again, there is no need for distortion correction for these. I prepare files for the internet, but spend more time preparing some files for print with paper profiling etc. I use Adobe Lightroom and Capture One software for post-processing.

South coast colours, mineral and silt rich river flowing into the ocean, Planet Iceland, aerial shots from 2-3k ft, Cessna 172

Sunset highlights - golden hour in the southern highlands and the low autumn sun highlights an old crater and part of the lava field, Iceland

Is there a place you've photographed that has particularly fascinated or marked you? If so, why?

I have a long list of places in my mind that have amazed me more than others. These include the Múlajökull glacier with its glacial kettle lakes, glacial kettles at Mirdalsjökull, the almost luminescent moss (technically it is lichen) patterns in the Icelandic highlands, the amazing patterns of glacial braided rivers along the South coast, especially south of Skaftafell and the Grímsvötn volcanic area at the Vatnajökull ice cap and alkaline lakes (like Magadi) in southern Kenya.

All of these places had something that somehow superseded my best expectations whether the bright colours of glacial lakes, the enormity and sheer scale of landscape’s wonder at Múlajökull and Grímsvötn or the intense colours and light in Kenya. In general Iceland is just one amazing place to fly and photograph, as its compact size allows you to see every kind/type of a landscape you can think of within a few hours. It is like a continent in miniature, with endless possibilities to find new views and ways to photograph them. I hope to fly and photograph in Greenland and South America, so hopefully the list of amazing places will keep growing and then of course there are more places in Africa, Australia, and North America to explore.

North Kenya, 2024, photo taken by Gurcharan Roopra @gurcharan

Full text in French can be found here.