For a long time, I wanted to see the amazing colours and patterns of Africa. This story started when I met the wonderful Gurcharan on board an airplane going back home from Iceland, of course :). It was when the seed of an idea of going and flying in Africa started growing and a few months later I was on board a jet taking me to Kenya.

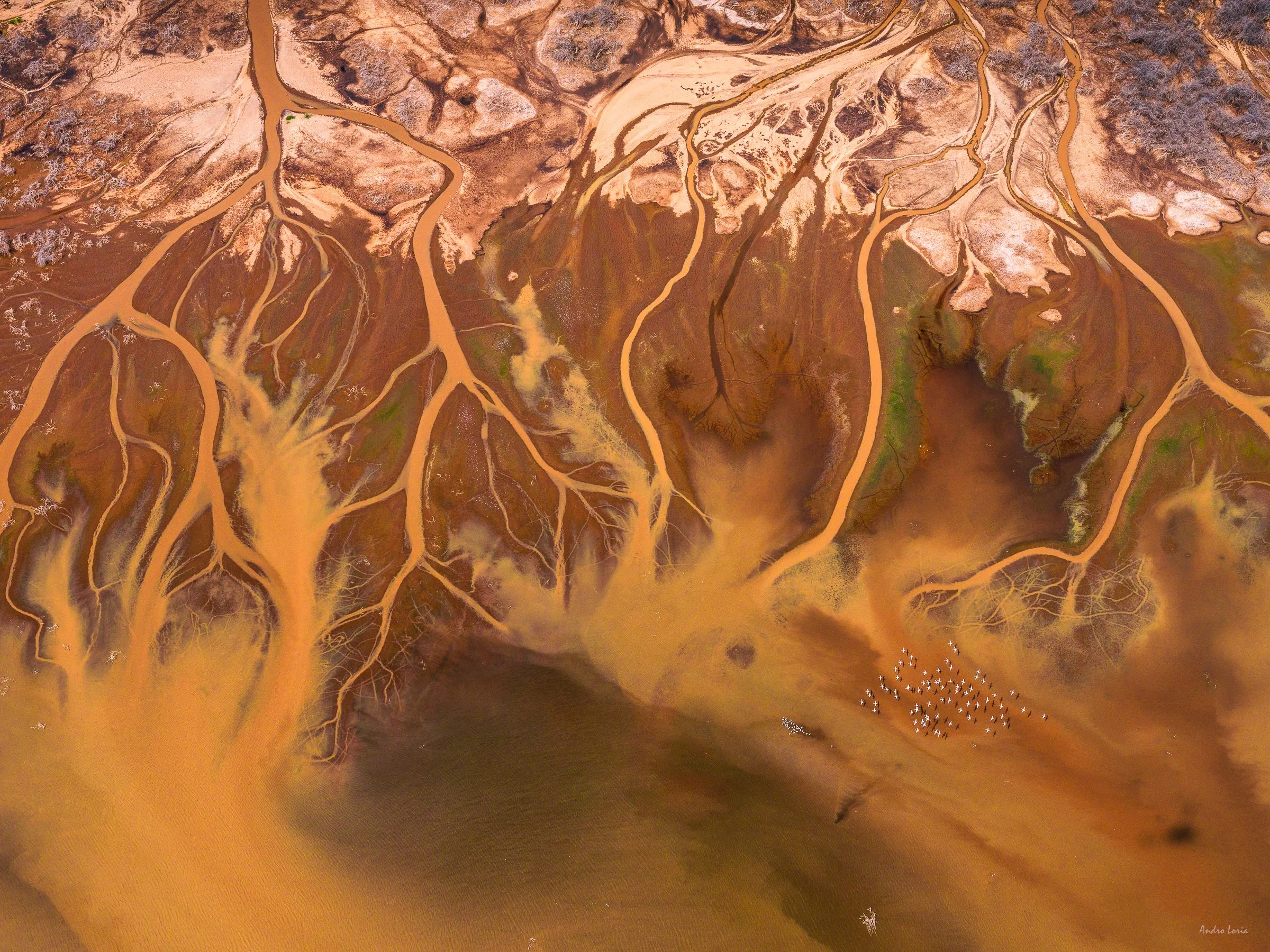

Flamingos flying over soda brine patterns formed by winds on the Magadi lake surface, cloud reflections on the top of the frame.

Most people think of the amazing wild nature that Kenya has on offer, with the Maasai Mara and Amboseli National parks coming immediately to mind in southern Kenya with the abundance of wild African animals and eons of photo-safari possibilities. But for me the main interest was elsewhere. Kenya lies on the East African rift, with its ancient and young volcanic craters, geothermals and alkaline lakes, outcrops of various geological formations and even outback desert dunes hundreds of miles away from the oceanic coast. So, my disclaimer here is that you will only find a few images of animals (elephants) in this post, and birds, such as flamingos, were photographed primarily as a reference scale and composition booster for the aerial shots.

Patterns of coastal streams at the Magadi lake area

Dry soda and soda brine patterns at the Magadi lake area

Flying in Kenya. The main difference flying in Kenya compared to Iceland was that we flew small helicopters. The R44 Robinson during trip to South (February) and the R66 when flying in Northern Kenya (November). The ability of flying slow, hovering, making stops pretty much whenever and wherever is needed, 4 to 5 hours range of flying on full tank make these helicopters wonderful machines and very comfortable to photograph from. On both trips the doors were off. Having two photographers on portside (front and back seats) allowed for seamless simultaneous shooting. We flew two separate trips – one to the South and one to the North from our base in Nairobi, around 8 and 10 hours respectively spread over two days for each trip.

Lake Logipi filled with rain water, soda brine patterns and clouds reflection on water. A flock of flamingos left of the centre.

Algae growth and some dead trees of the coast of Lake Bogoria.

Yes we saw a lot of elephants 🐘🐘🐘 and here is the proof :) Shot from R44 🚁 and R66 🚁 on both trips.

Another big difference of flying in Africa is of course the weather, most of all the heat. Especially when flying over salt flats and lakes during the day. The weather is mostly very stable, which was a pleasant surprise to me for change, but the heat is something one has to be aware of. Temperatures over 40 C whilst flying in doors-off helicopters and being constantly dried by hot air flow require you to stay hydrated, so a large thermal flask of water is a must to have with you.

Abstract nature - dry stream beds, Suguta Valley

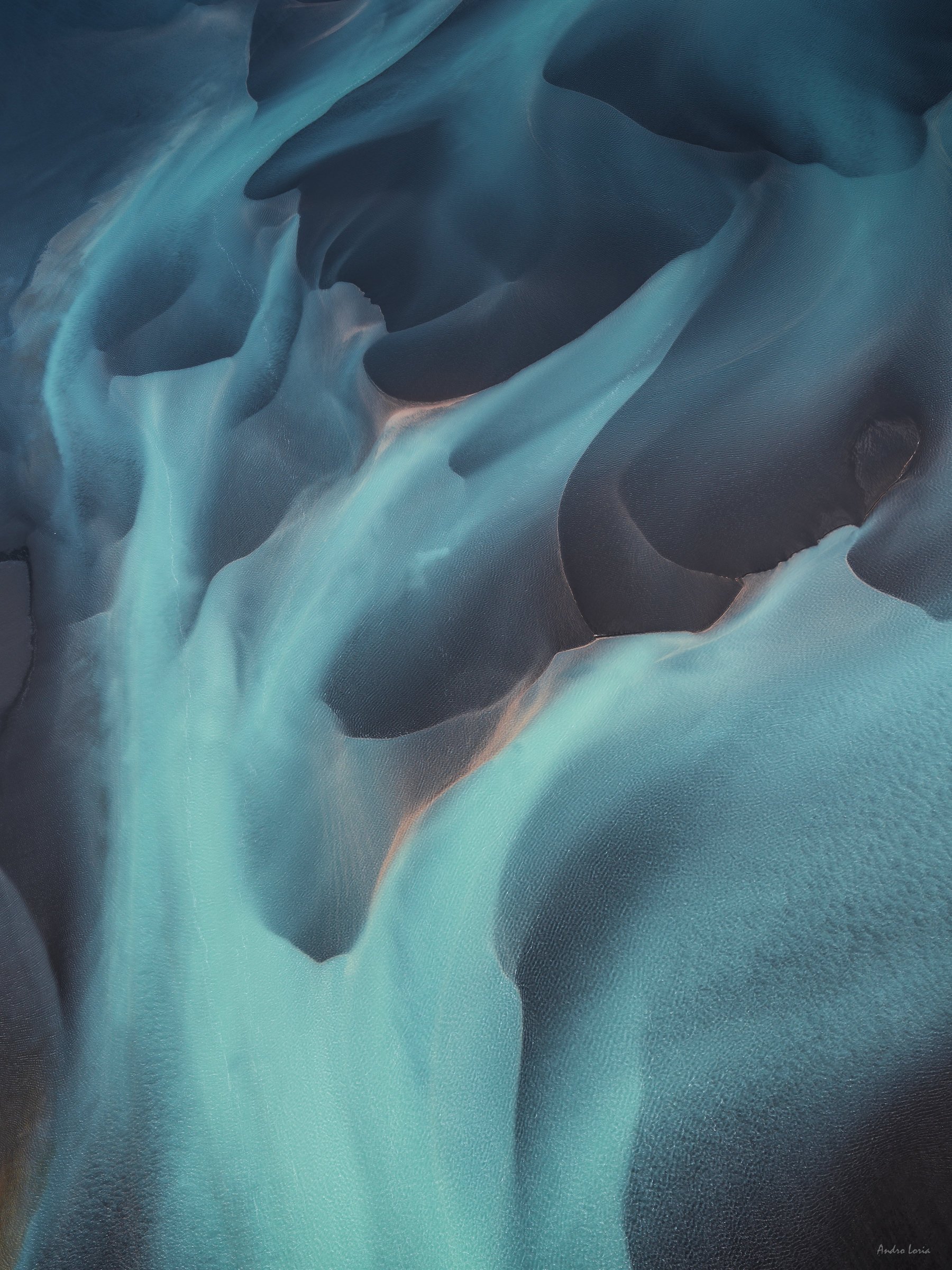

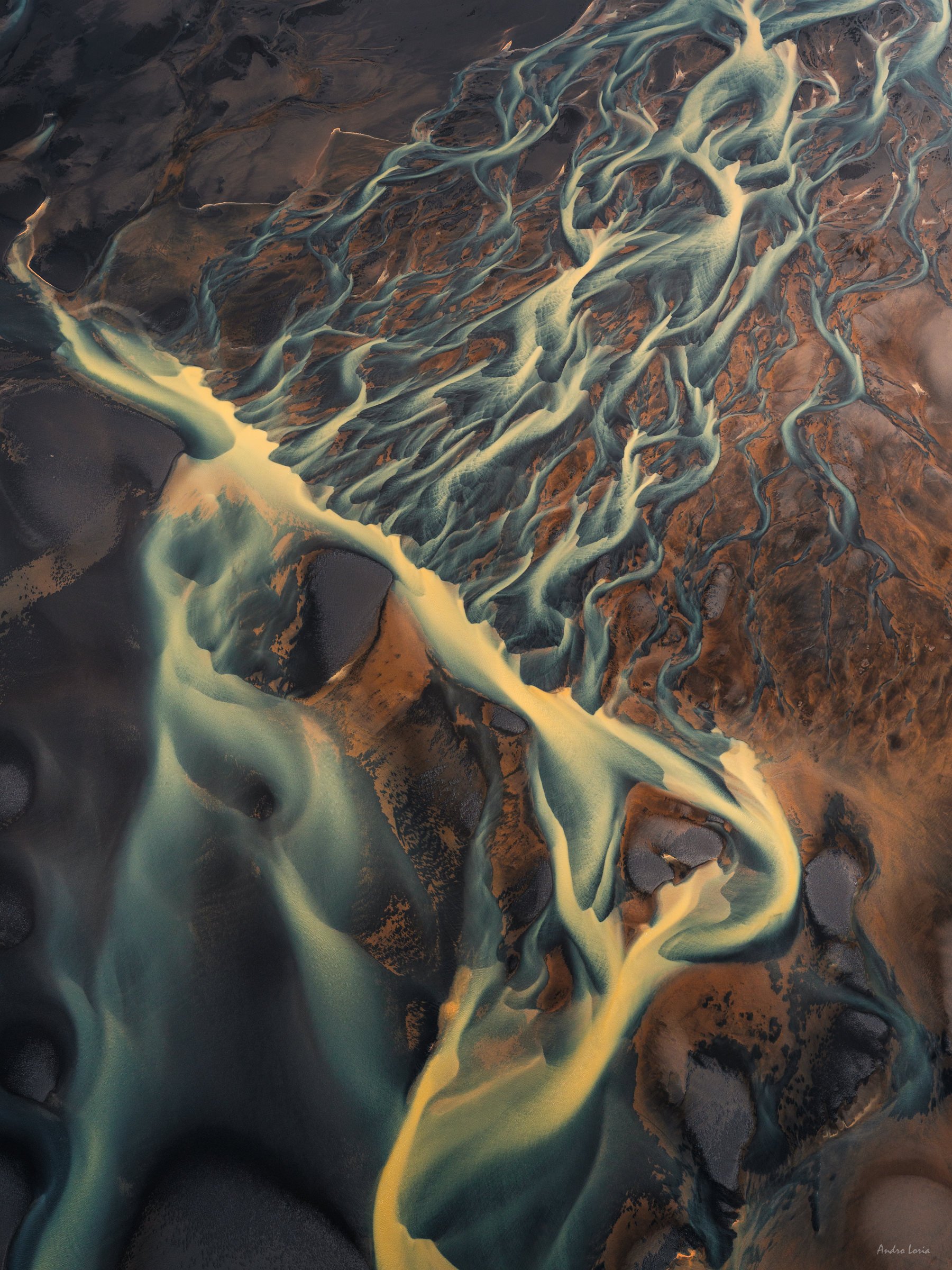

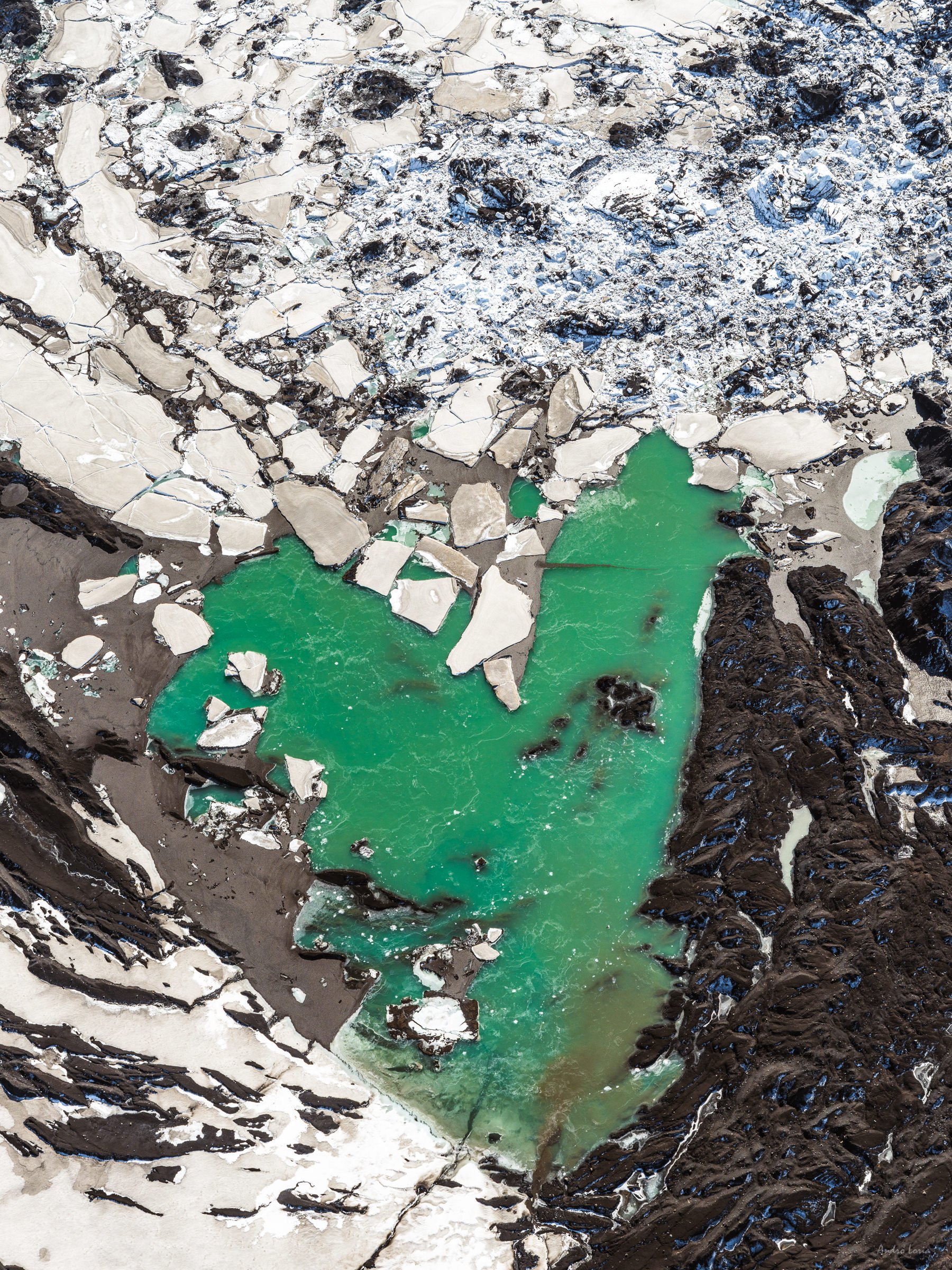

Turkana – Turkana lake is the 4th largest salt lake in the world. The lake is more than 290 kilometres long, 30 metres deep and 32 kilometres at its widest point. Most of the lake is within the borders of Kenya with only a small northern part of it extending into Ethiopia. Lake Turkana is famous for its greenish-blue (jade) colour of water that is created by algae. Its water is not as alkaline as others (pH 8.5–9.2), but has very high levels of fluoride. The lake is home to many species of fish and a large amount of Nile crocodiles. Winds can be very strong at Lake Turkana, as the water mass warms and cools more slowly than the land and sudden, violent storms are frequent.

Nabiyotum volcano crater at the southern tip of Lake Turkana in Northern Kenya, last erupted in 1921, the volcano is ~2.2k ft high, with an inner crater diameter of ~2.5k ft, the outer rim of volcanic conus is ~4.8k ft.

Dry soda and soda brine patterns at Lake Magadi.

“Crocodile” rock at the Suguta valley at sunset, ~1200 feet long and 100 feet wide. This rock sits in the middle of the plane, open san-blasting winds and sun. A few last sunset rays painted it very nicely.

Take off patterns, flamingos flying near the coast of Lake Bogoria.

Rift Valley Soda Lakes – The East African Rift, on a boundary of the continental rift (African, Nubian and Somali plates), has many lakes, but the smaller ones stretching from Tanzania to Kenya and into Ethiopia on the East of Victoria microplate are a chain of shallow soda lakes such as Natron, Magadi, Bogoria, Logipi, followed by the salt lake of Turkana located in the Eastern (Gregory) Rift Valley.

Abstract Africa, Lake Magadi area

Lake Magadi - a saline, alkaline lake, (pH 10) approximately 100 square km in size, that lies in an drainage basin formed by a graben (depression or trench in crust) at the lowest point in the eastern part of the Gregory Rift Valley. Lake Magadi is one of the most saline, but also is one of the smallest, alkaline lake sumps in the Rift Valley. The lake is about 600 metres above sea level and is a great example of a "saline pan". With no water leaving the lake by streams or rivers evaporation is the only way water levels are reduced, especially during the dry season. This creates a large array of colourful dry soda areas with patterns and colours provided by pigments from algae, plankton, bacteria and tiny crustaceans (like brine shrimp). The cyanobacteria and crustaceans are a particularly preferred food source for flamingos, which acquire their colour from metabolising pigments from their food.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Bogoria.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Magadi. Pink colour from algae bloom.

Patterns of coastal streams, Lake Magadi area.

Old crater filled by sand from nearby dunes, Suguta Valley.

Amazing colours and rocks of the Painted Valley. Suguta Valley

Dunes at sunset, Suguta Valley. Gurcharan is testing his Nikon’s sandproofing, right off centre.

Dry soda and brine patterns, Lake Magadi.

Flamingos flying over soda brine patterns formed by winds on theMagadi lake surface.

Flocks (flamboyances) of flamingos flying through a sandstorm near the coast of Lake Logipi

“Fireflies in a magic forest” - dry soda patterns, brine and water of Lake Magadi.

"Sword fish" crater... Colours and texture of one of the many old amazing craters/volcanos at the northern Kenya Rift, Suguta Valley. The crater is ~0.3 miles across (400-450m). The crater is just east of Namarunu – the large shield volcano flanking along the axis of the East African Rift at the valley’s south west

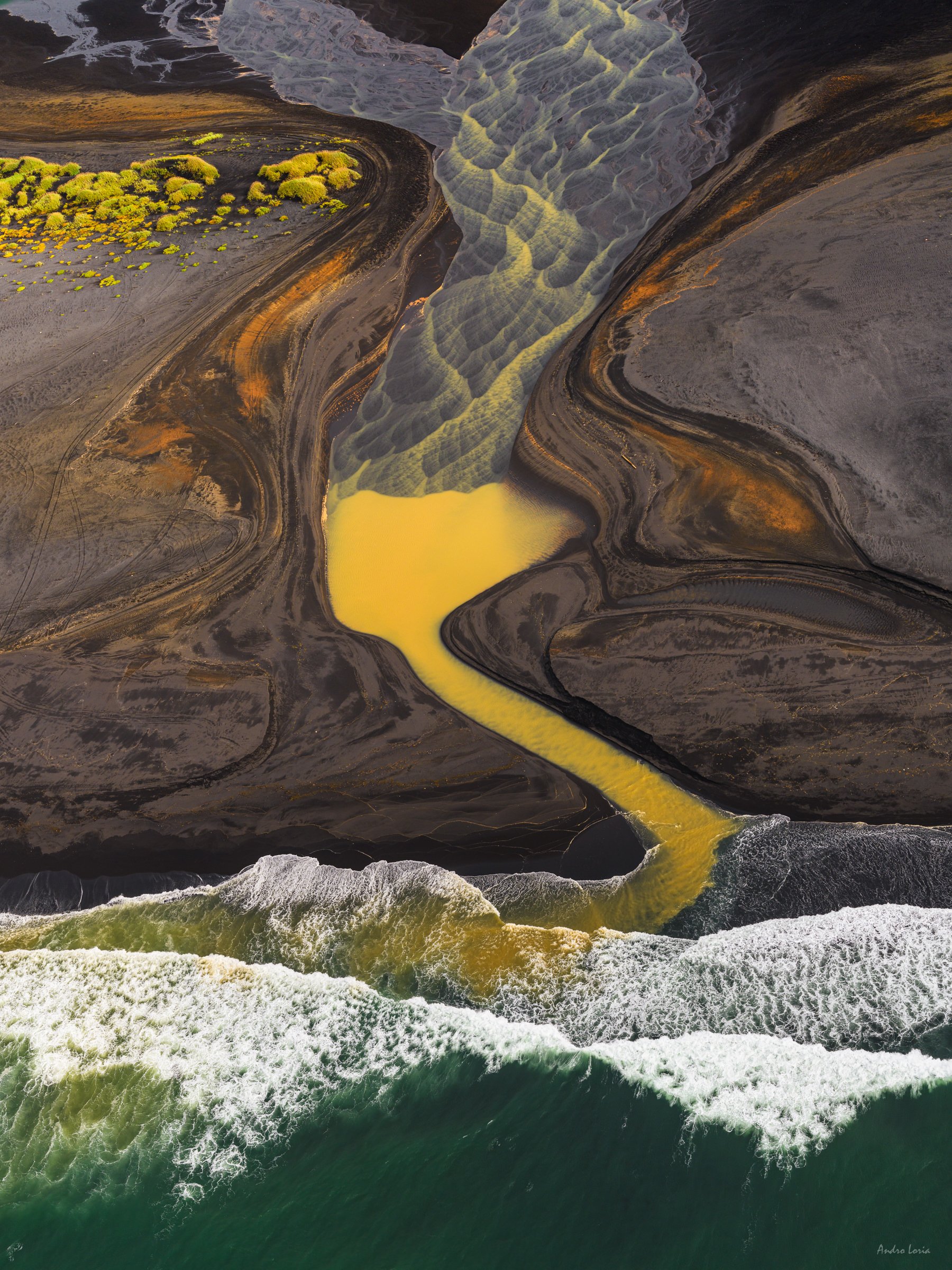

Natron – a large soda lake (pH 9–10.5). Most of the lake is located in Tanzania, so we did not fly over that part. Yet the northern coastline is rich with patterns of dry soda, with some deep blue shades.

Take off patterns, flamingos flying near the coast of Lake Bogoria.

Bogoria – is the northern most of Kenya’s soda lakes with water pH ~10.5. The lake is extremely salty and has a saline content double that of sea water density. Like the other lakes, volcanic minerals enrich Bogoria’s waters with algae, providing an environment for hundreds of thousands of the lesser flamingos. The shores of the lake are fringed by hot springs and geysers.

A Maasai warrior stands on the red alkaline waters of Lake Magadi. See how shallow this part is with a soda crust under the water.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Logipi.

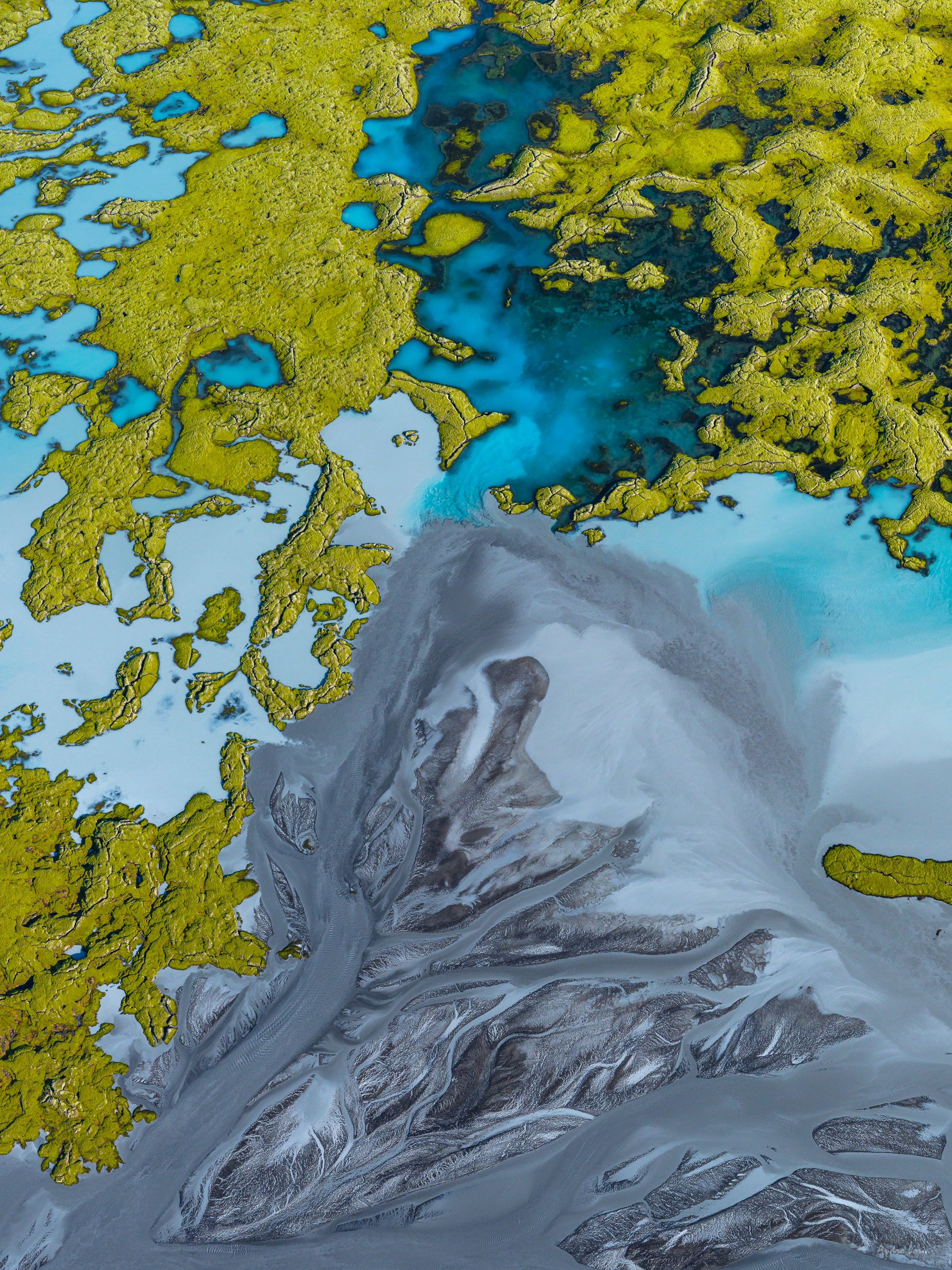

Lake Logipi - a minor lake in the northern Rift Valley, it lies at the northern end of the Suguta Valley. Lake Logipi is about six kilometres wide and three kilometres long, it has a maximum depth of five metres and is separated from Lake Turkana by 'The Barrier', a group of young volcanic mountains that last erupted in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Cathedral Rock in the Suguta Valley, northern Kenya Rift. The Rock is made of a young basalt flow (black) and associated tuffs (orange). This volcanic island is surrounded by Lake Logipi, a saline shallow lake with numerous flamingos.

In the middle of the Logipi lake bed there is a rocky island, Naperito Rock, about 370 metres high, known as the Cathedral Rock, from which hot springs of saline help to maintain the presence of water even in periods of extreme drought.

Dry soda patterns and stream, Lake Magadi.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Bogoria.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Logipi.

Dry soda patterns, Lake Magadi.

“Face mask” of one of the Andrew’s volcano craters

Andrew’s volcano is one of the numerous volcanic craters dotting the volcanic ridge, known as The Barrier, that separated the Suguta Valley from Lake Turkana several million years ago. The last eruption took place just over 100 years ago.

Patterns of coastal streams at Lake Magadi.

Old crater, part of Namarunu, the large shield volcano at the Suguta valley’s south west.

Suguta Valley, one of the hottest places on Earth, nicknamed "The Valley of Death", with huge granite rocks that combine with piles of volcanic ash, gorges of layered rock and miles of sand dunes. Probably one of the most amazing places I have seen so far, it is packed with coloured craters and rock formations. At its northern part there are craters and volcanoes of The Barier and Andrew’s volcano, with Namarunu – the large shield volcano flanking along the axis of the East African Rift at the valley’s south west.

Algae growth and some dead trees of the coast of Lake Bogoria

Dry soda and brine patterns, Lake Magadi.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Logipi.

Old crater, part of Namarunu – the large shield volcano at the Suguta valley’s south west. Basalt black with orange tuffs, reds and yellows of iron and sulphur plus some sand blown from nearby dunes. Purple and lavender tones come from manganese deposits.

Dry soda, brine and streams at the edge of Lake Magadi.

Old crater filled by sand from nearby dunes, Suguta Valley

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Logipi.

Sunset at dunes, Suguta Valley

Old crater, part of Namarunu – the large shield volcano at the Suguta valley’s south west.

Flamingos flying over the rain water filled Lake Logipi.

The Suguta valley is drained by a seasonal stream, the Suguta River, which in the rainy season forms the temporary Lake Alablad, a dry lake that combines with Lake Logipi at the northern end of the valley. In the dry season saline hot springs help maintain water levels in Lake Logipi.

Dry soda, brine and streams at the edge of Lake Magadi.

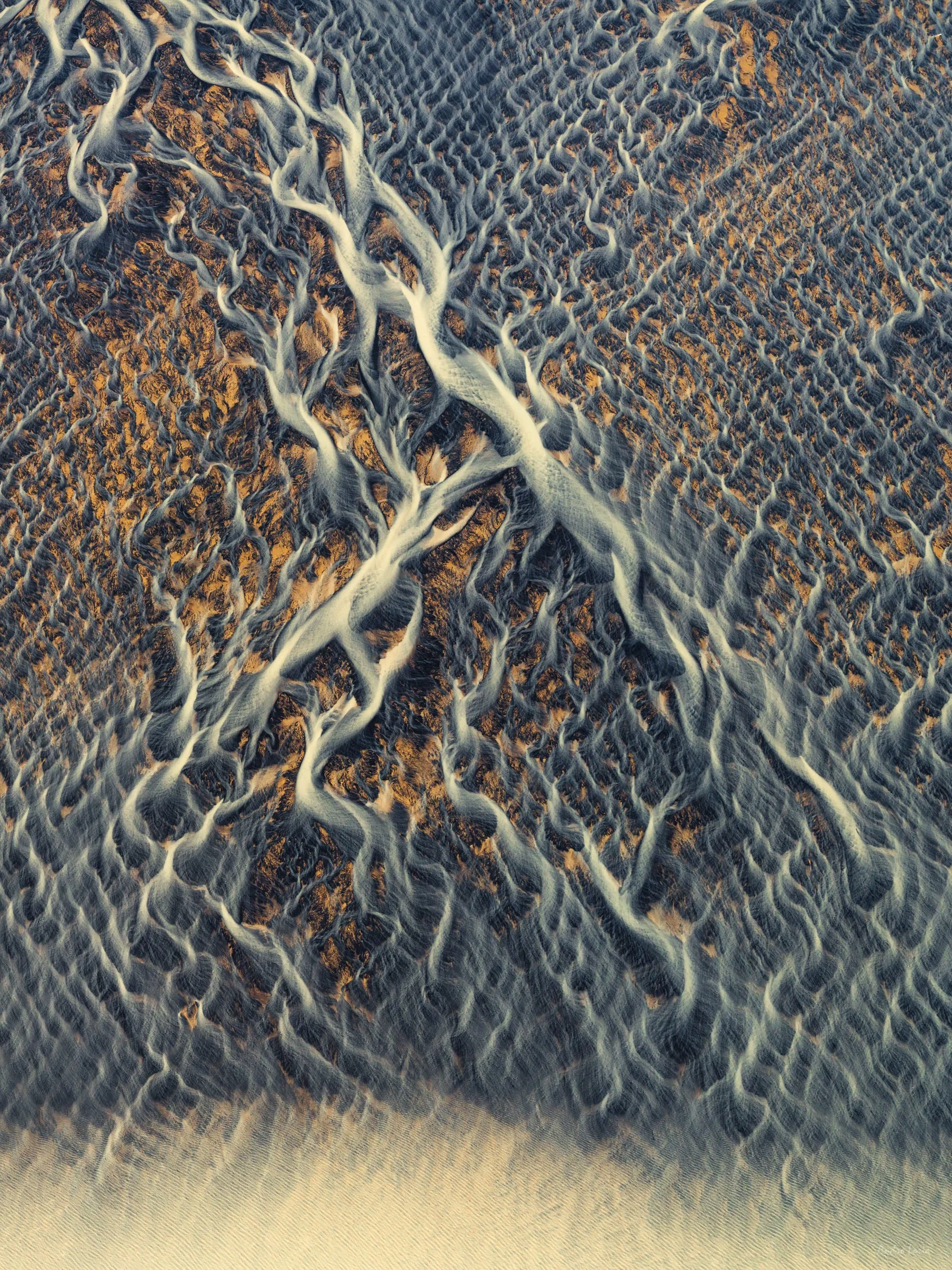

Patterns of rain water streams, Suguta valley.

Dry soda patterns, north shore of Lake Natron.

"Sword fish" crater east of Namarunu – the large shield volcano at the valley’s south west.

Dry soda, brine and streams at the edge of Lake Magadi.

Flamingos flying over the coast of Lake Bogoria.

Flamingos flying over soda brine patterns formed by winds on Lake Magadi’s surface.

Cameras and lenses – I used two Fujifilm GFX100 bodies, one with 45-100 mm lens and another one with 100-200 mm lens. I use my cameras on manual, playing with the zoom, focus and aperture with a set shutter speed (1/1000) and leaving ISO on auto between 100-400 or 100-800 at lower light. The automatic focus on the GFX100 works great if there is enough texture and contrast of colours below me on the ground and works less well when shooting river/lake patterns due to light reflections. I typically shoot between f5.6 – f14 and 1/1000 shutter speed. For top-down shots, the faster the shutter speed you use the better. The helicopter can slow down, but adds a lot of vibration.

Flamingos flying over the rain filled Lake Logipi.

Before and during the flight – I remove the lens hoods, they take too much air pressure and can knock your lens off in the wind whilst flying. The worst case scenario is that the hoods will get ripped off your lens and fly away. If you are in a helicopter, you really do not want that to happen. I do not use wide lenses - you will have parts of the airplane and/or helicopter in all of your shots. I make sure that spare batteries are easy to reach (and stashed away) in my pocket(s). The same goes for SD cards. Most of my photographs were made from 2,000 to 3,000 feet altitude, although on occasion it was higher, e.g. when the shot was over the top of a large crater or rock formation like Nabiyotum volcano crater.

I would like to say huge thank you to Shompole Wilderness (who also have great hide set-up to photograph wild animals - see their Instagram account) and Desert Rose (a beautiful oasis in mountains decorated throughout with amazingly carved wood) for their amazing hospitality, which we enjoyed in the south and north of Kenya respectively. Massive thanks to our amazing pilots, Marc and Peter, and of course the amazing Gurcharan Roopra for booking a seat next to me on Iceland Air and then guiding and sharing the flights with me over his amazing country.